We all remember the magic mirror belonging to the evil queen in the fairytale, Snow White. Each day the queen would position herself in front of the mirror and ask, “Mirror, mirror, on the wall, who is the fairest of us all?” And the mirror would reply, “You are, O Queen.” The queen would be reassured for the moment, content in the mirror’s lie and its acquiescence to her vanity.

Throughout history, the mirror has been one of the most prevalent and potent metaphors for the folly of human vanity. One of the foundational Western myths, for example, is the story of Narcissus who fell helplessly in love with himself when he discovered his reflection in a woodland pond. So taken was he with the beauty of his own image, he could not leave the pond and so died there.

Today we, too, seem to be obsessed with our own images. We wouldn’t think of leaving the house without first checking ourselves in the mirror. Lifts in buildings have mirrored walls so we can pass the time by looking at ourselves as we ascend or descend. There are mirror apps for our phones. And our mobile phones are the new mirrors, providing us with the instant ‘selfies’ that we can enhance (or delete) before sharing them with the world. We spend countless billions on lotions and potions in attempts to beautify ourselves and to ward off the aging process. Beauty and youth are idealized and idolised in glossy magazines, on the big and small screen, and across social media. And the way to happiness is often touted as being as easy as a few deft swipes of the plastic surgeon’s knife. The idea is that we’re only as worthwhile as our outward appearance. If we don’t look good, we cannot be happy. In this way, the mirror is powerful because we allow it to have power.

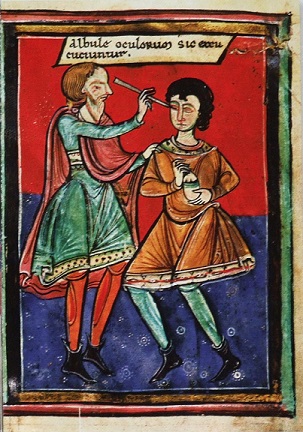

And its power over humans started a long time ago. Archaeologists have found evidence of the earliest mirrors being simply polished surfaces of natural materials – rocks like obsidian, for example – which could reflect back an image, albeit a hazy one. With time, the crafting of metals – copper, silver, gold – gave the self-viewer a slightly clearer idea of him/herself but it was still a rudimentary reflection. The glass mirror – the closest ancestor of our contemporary mirrors – is recorded from Roman times but it was really during the Middle Ages that the quality of glass became good enough to return a clear reflection. Around that time, the manufacture of a much smoother glass enabled a relatively blur-free surface to be achieved and its reflective ability was increased by backing the glass with a metal such as gold leaf or a silver-mercury combination.

The medieval mirror par excellence was the work of Venetian glassmakers on the island of Murano. Their backing material of choice was kept secret for many decades but it was known to include mercury in the gilding process which, of course, made the final product ‘problematic’. Still, that didn’t dampen the general enthusiasm for mirrors (though, of course, their cost made them a luxury item for the wealthy only). After that, the reflective quality continued to improve over the centuries as production methods advanced the clarity of glass.

As far as the mirror was concerned, there was no looking back!