There’s a heatwave in Sydney at present. And sleeping soundly – which, for me, is often elusive at the best of times – is difficult as we toss and turn in the merciless humidity that grips until the early hours of a new day. In these conditions, dreaming is a distant memory but it is generally held that dream-filled sleep is essential to our overall wellbeing . Dreams, as we all know, are complicated. Sometimes they are pleasant, sometimes terrifying, but always they leave us with fleeting and fractured impressions of our sleeping subconscious after we wake from them, and a quiet knowledge that there is something more going on with us, beyond our waking perceptions.

Interest in dreams goes back a long way into our human history; and throughout the ages there has been no shortage of authors putting quill to parchment for the purpose of exploring the dream-state more deeply.

Cicero, the great Roman orator and statesman, and consul of Rome in 63BC, is among the many who wrote about dreams. In fact, his Somnium Scipionis (The Dream of Scipio) became one of the most influential works on dreams for later medieval writers. Cicero’s story of the dream of Scipio Africanus – in which the subject’s grandfather appears to him and gives him insights into such heady topics as cosmology and the immortality of the soul – made such an impression on the early medieval writer, Macrobius, that he wrote a detailed commentary on Scipio’s dream, developing the elaboration into a classification method for dreams in general.

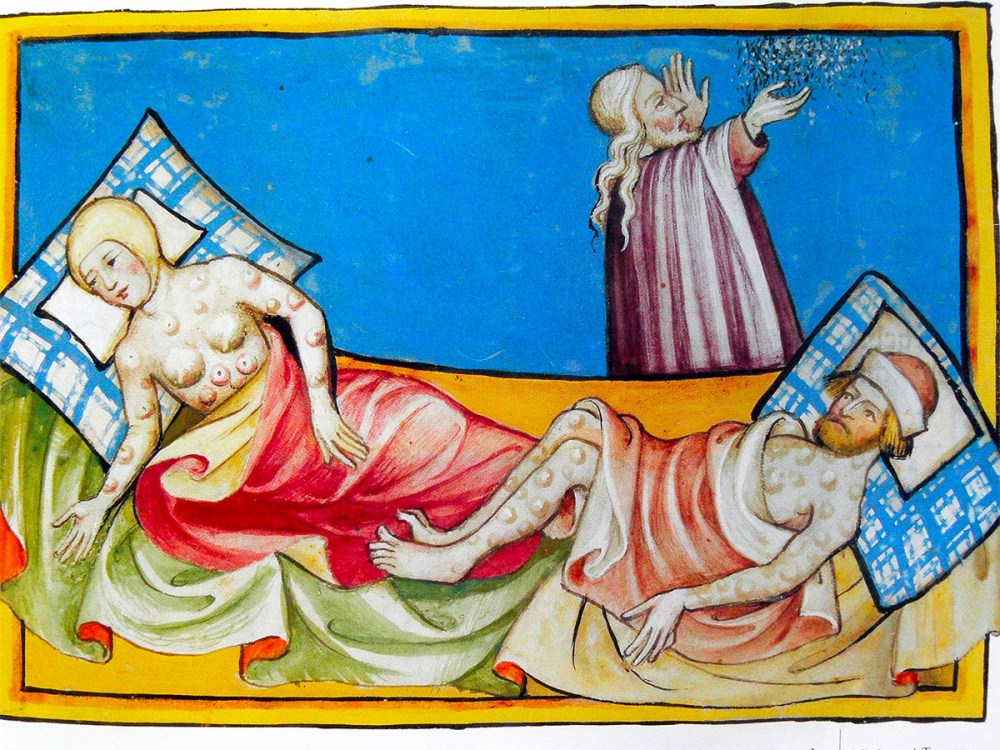

Macrobius’s method distinguished 5 types of dream. The first two types (nightmare and apparition) he declared as ‘insignificant’ because he believed them to be non-predictive/non-prophetic (and, therefore, of no practical use to one’s present or future life). Such dreams, he said, were brought about by day-time anxiety or stress or, in particular, over-indulgence in the wrong kind of food and drink.

The next three types in the classification, however, were of great significance:

- The somnium or enigmatic dream in which strange shapes and symbols represent important meanings that must never be ignored but always carefully interpreted.

- The visio or prophetic visionary dream which is a clear glimpse or insight into what is to come.

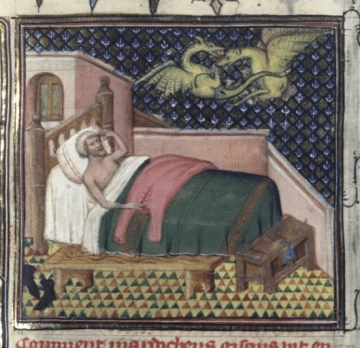

- The oraculum in which someone of importance and/or great wisdom (from the past or present, dead or living) appears to the dreamer to impart information or advice.

Such credence was given to Macrobius that, in the later Middle Ages, a whole genre of dream-vision poetry developed with his classifications as the base and inspiration. Great medieval authors such as Chaucer (who not only wrote many dream-vision poems but actually mentions Macrobius’s Scipio in at least three of them) and Guillaume de Lorris (Romance of the Rose) were masters of the genre. Even Dante’s epic The Divine Comedy is a vision of the world beyond death.

Today, of course, most writers are cautious about employing the dream device but, for medieval authors, it was regarded as a skilful way of bringing together the worlds of reality and imagination. Then, too, the division between the material and the spiritual was much more fluid, less stringently applied than in our own matter-of-fact time. Now, the dream (and even sleep itself) has been down-graded to a distant second-place behind our ‘real lives of busyness’. There is little time to ponder our dreams when all waking moments are taken up by the bright screens of modern technology.

Something to think about as you fall asleep tonight … unless, of course, you’re stuck in a heatwave, or you’ve over-eaten beforehand!