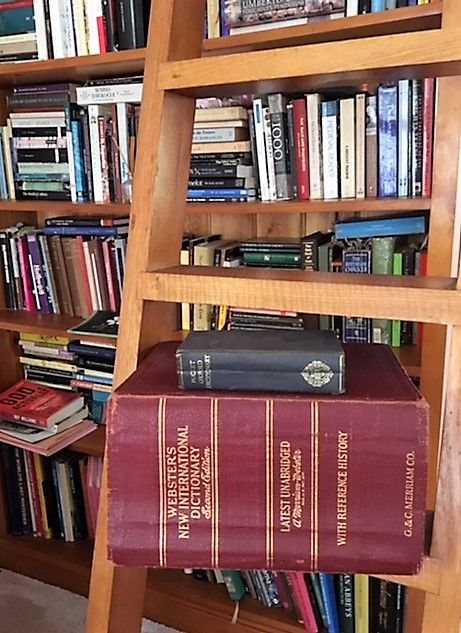

I love all the books (and there’s a lot of them) in my home library but the giant-sized Webster’s Dictionary (Unabridged) is one of my special favourites – all 3562 of its tiny-print pages. Each of its entries gives not only the current meaning of a word but also its origin and change/s in denotation and connotation over the centuries. Some words have flipped their meanings entirely. ‘Silly’, for example, now means ‘unwise, in want of understanding or common sense, foolish’; but the word originally came from the Old English (Anglo-Saxon) sælig meaning ‘happy, good, blessed’. We can easily imagine that part of the reason that ‘silly’ took a dive from the positive into the negative was the rise of rationalism and scientific dominance over religion.

On the other hand, ‘pretty’ has experienced a lift in meaning. In the original Anglo-Saxon prættig meant crafty, sly, deceptive. Well, maybe we can fill in the gaps as to how the more familiar meaning of ‘pleasingly attractive, good-looking’ evolved.

But, the big Webster’s is getting old now and, while its 1932 publication date has allowed me to dip into it for invaluable insights about the origins and evolution of much of our English language, the vernacular is a very fluid thing. This is why the modern dictionary compilers are always adding, and sometimes subtracting, and often re-defining, words and their meanings. Just this year (2023) Merriam Webster added 690 words and/or phrases, among them ‘cakeage’ which, following its earlier cousin, ‘corkage’, means a fee charged by a restaurant for a customer bringing in a cake to share with other guests at the table, rather than buying dessert from the restaurant; and ‘digital nomad’ which is used to describe a person working remotely whilst travelling. And then there’s the self-explanatory ‘nearlywed’ for those living together.

Similarly, the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) added around 700 words and phrases in the most recent quarter of 2023. There’s ‘side-hustle’, referring to a way of earning income on top of one’s main job; and ‘jabbed’ (and even ‘double-jabbed’ and ‘triple-jabbed’) in acknowledgment of life in a post-Covid world. And ‘gaslighting’, a word which had its origin in the 1930s play Gaslight by Patrick Hamilton (and more widely spread by the 1940 movie of the same name), has well and truly crossed into mainstream language with its recent inclusion in the OED. It’s defined as lying to someone for the purpose of mentally or emotionally manipulating them.

Now, that’s certainly not pretty, is it? (But it IS prættig!).

was the great visionary, Hildegard of Bingen. Born in Germany’s Rhineland in 1098, Hildegard was not only a prominent religious figure of her day but also – as her considerable writings and works demonstrate – an expert on natural science, medicine and herbal treatments, cosmology, poetry and music. Further testament to her influence is that many of her writings (and musical compositions) survive to the present day. Hildegard’s works are not ‘easy reads’ but a lot of her ideas resonate with our current interests, particularly our concerns over climate change and caring for our planet.

was the great visionary, Hildegard of Bingen. Born in Germany’s Rhineland in 1098, Hildegard was not only a prominent religious figure of her day but also – as her considerable writings and works demonstrate – an expert on natural science, medicine and herbal treatments, cosmology, poetry and music. Further testament to her influence is that many of her writings (and musical compositions) survive to the present day. Hildegard’s works are not ‘easy reads’ but a lot of her ideas resonate with our current interests, particularly our concerns over climate change and caring for our planet.

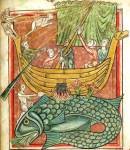

which mariners can “come ashore”. Once there, Caxton explains that it is not unusual for the seamen to light a fire on which to cook their food. However, the heat of the cooking fire eventually distresses the whale enough that he must dive down under the water to cool himself, thereby taking all the mariners with him to their death. The symbolic interpretation of this is that the whale is as deceitful as the devil, luring men to death (spiritual and physical) when they fail to be alert to the deception, and fall for easy and comfortable options.

which mariners can “come ashore”. Once there, Caxton explains that it is not unusual for the seamen to light a fire on which to cook their food. However, the heat of the cooking fire eventually distresses the whale enough that he must dive down under the water to cool himself, thereby taking all the mariners with him to their death. The symbolic interpretation of this is that the whale is as deceitful as the devil, luring men to death (spiritual and physical) when they fail to be alert to the deception, and fall for easy and comfortable options.