In 1934, in the dark recesses of an old English family library, a rare fifteenth century manuscript came to light. Scholarly investigation revealed it to be what is now known as The Book of Margery Kempe, the life story of an extraordinary medieval woman who answered “yes” without hesitation when she thought God was calling her. Today, some regard her as a mystic; others as a sick, or attention-seeking woman but, whatever the truth, Margery gives us a surprising lesson in devotion and perseverance.

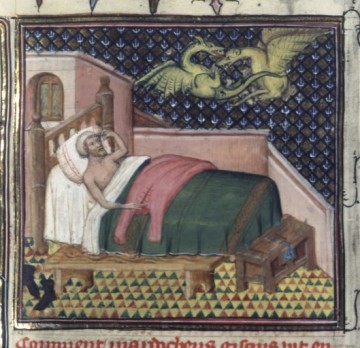

Margery was born in 1373 in the Norfolk town of King’s Lynn where her father, John Brunham, had been the Mayor for five separate terms. At twenty years of age Margery married John Kempe and within a year of the marriage, had given birth to her first child. She went on to have a further thirteen children but the first birth was especially decisive as, immediately following it, Margery experienced what we now would probably describe as a post-partum psychotic episode but which Margery herself describes as being tormented by devils. Margery explains that the relief from this episode came in the form of a personal visit from Jesus and this unexpected encounter set her on her life’s quest of serving God.

Margery did nothing by halves. Believing that Jesus had appeared to her during her illness, she emerged from her sickbed and began to spend a great amount of time praying, arising at two or three in the morning and making her way to church where she would pray until midday and then again in the afternoon. She confessed to a priest twice and, sometimes, three times a day, in particular seeking forgiveness for an early sin which she had avoided confessing for many years. She adopted stringent fasting and the wearing of a hair-shirt made from the coarse cloth on which malt was dried. It was in these early years, too, that Margery reports receiving the ‘gift of tears’.

This gift, in particular, with its associated crying and wailing at even the mention of Jesus’ name, saw Margery shunned by many who witnessed the extreme behaviour. Such was her disruptive influence that some priests refused to allow her in the church when they were to preach. But Margery persisted in her devotions, feeling that her original “yes” to God was a promise on which she could not renege. She also felt compelled to embark on numerous and extensive pilgrimages and travelled, over several years, to the Holy Land, Rome, Assisi, Santiago de Compostela, Norway and Germany, as well as important pilgrimage sites throughout England. This was an amazing undertaking in the 14th century and even more remarkable for a (sole) woman.

Then, as now, Margery’s travels and general behaviour garner divided opinions on the authenticity of her mystical calling. That is, while there is no doubt of her devotion, her motivation for, and expression of it remain a matter of considerable debate. Putting this debate aside, however, there emerges a wonderful and unexpected consequence of her “yes”…

From The Book we know that, though Margery was illiterate, she managed to dictate her story to an unidentified scribe. Six hundred years after she lived and was almost forgotten, the finding of the manuscript of her life story gave the world the great gift of the first autobiography in English.

, with its strange list of ‘gifts’, evokes the medieval world. Again, this carol is more recent, its words having been first published in England in 1780; but the idea of such a list can be found in the provincial songs of many earlier compositions. Additionally, “a partridge in a pear tree” does have very close links with the allegorical/moral entries in medieval bestiaries. (I’ve written about bestiaries in another post but, for those who don’t know, the medieval bestiary is a type of compendium of beasts and animals, real and mythical, accompanied by a symbolic interpretation and a moral lesson, particular to each beast). There, the partridge is described as a deceitful bird because of its practice of stealing the eggs from the nest of other birds, and of then hatching them. This was never to the partridge’s advantage, however, as, once hatched, the baby birds would recognise the call of their true mother and would fly to her. The associated allegorical meaning was that the partridge stood for the Devil and his stealing of souls (into sin) but, eventually, when the sinners recognised God as their true creator, they would repent, leaving the Devil empty-handed.

, with its strange list of ‘gifts’, evokes the medieval world. Again, this carol is more recent, its words having been first published in England in 1780; but the idea of such a list can be found in the provincial songs of many earlier compositions. Additionally, “a partridge in a pear tree” does have very close links with the allegorical/moral entries in medieval bestiaries. (I’ve written about bestiaries in another post but, for those who don’t know, the medieval bestiary is a type of compendium of beasts and animals, real and mythical, accompanied by a symbolic interpretation and a moral lesson, particular to each beast). There, the partridge is described as a deceitful bird because of its practice of stealing the eggs from the nest of other birds, and of then hatching them. This was never to the partridge’s advantage, however, as, once hatched, the baby birds would recognise the call of their true mother and would fly to her. The associated allegorical meaning was that the partridge stood for the Devil and his stealing of souls (into sin) but, eventually, when the sinners recognised God as their true creator, they would repent, leaving the Devil empty-handed.